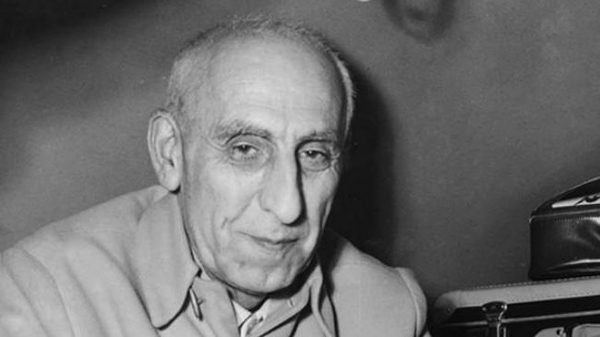

It’s not easy to write about Dr. Mossadegh as the second most important man in Iran’s history, since many consider him to be the Iranian national hero of all time. It could neither be hidden to anyone how his efforts in re-establishing Iranian national rights and interests have been valuable. There is no doubt that his undertakings for the establishment of common rights of the Iranian people represent a golden page of this man’s patriotism in our history; even though the partisans of the monarchy have always criticised his doings as a sign of excess and authoritarianism. Meanwhile, what emanates from these eulogies, as well as critics, is that he had an indisputable influence as Iran’s second man during this sensible period of the history of our country.

It’s not easy to write about Dr. Mossadegh as the second most important man in Iran’s history, since many consider him to be the Iranian national hero of all time. It could neither be hidden to anyone how his efforts in re-establishing Iranian national rights and interests have been valuable. There is no doubt that his undertakings for the establishment of common rights of the Iranian people represent a golden page of this man’s patriotism in our history; even though the partisans of the monarchy have always criticised his doings as a sign of excess and authoritarianism. Meanwhile, what emanates from these eulogies, as well as critics, is that he had an indisputable influence as Iran’s second man during this sensible period of the history of our country.

Mohammad Mossadegh was born during the spring of 1882 in an aristocratic and affluent family of the Qajar era in the Sangelaj area of Teheran. His father was Mirza Hedayatollah Ashtiani, Nassereddin Shah’s Finance Minister, of the Mostowfi-Ashtiani families of the Bakhtiari tribes. His mother was princess Najm-o-Saltaneh, the grand-daughter of Abbas Mirza, heir to throne, cousin of Nassereddin Shah and daughter of prince Firooz Mirza Nosrat-o-Dowleh. This family link helped Mossadegh become the exchequer of the Khorasan province during the reign of Mozaffareddin Shah.

It was after this event that Mossadegh decided to enter the world of politics. He left the Khorassan exchequer position to Mirza Reza Gorgani, who himself was the treasurer of the Saveh and Kurdistan provinces. Abdullah Mostowfi, the historian of the time, writes: “As Mossadegh had an amicable relation with my brother Mirza Reza, he left the job in Khorasan to him in 1280 (1901). Mossadegh, who was 19 at the time, chose Zahra, daughter of Mir Seyyed Zeynol-Abedin Zahirol-Eslam, the third person-in-charge of the Tehran Friday sermons, as wife. Zahra, in turn, had the title of Zia-o-Saltaneh. This title was bestowed upon her after her mother. This mariage lasted for 64 years until the end of the couple’s life. Mossadegh and his spouse had two sons, Ahmad and Gholam-Hossein, and three daughters by the names of Zia Ashraf, Mansooreh and Khadijeh.

Mossadegh was sent to France in 1908 to continue his studies and, having finished them at the Political Science Faculty of the University of Paris, he left for Switzerland to obtain his doctorate in law at the University of Neuchâtel. He wrote his thesis on the subject of heritage according to Islamic tradition. Thus, he was the first Iranian to have received a doctorate in law.

Mossadegh returned to Iran in 1914 and started teaching at the faculty of political sciences at the University of Teheran. It was during this period that he wrote works such as “Iran and Capitulation,” ”Order in Courts of Justice,” and “Private Companies in Europe.”

A year later, he became a member of the Moderation Party and then of the Democratic Party. In October of the same year, the parliament made him a member of the Commission for the Equivalence of Mandates for two years.

Mossadegh’s return to Iran was simultaneous to the beginning of World War I. As he had already spent some of his career in finance in Khorasan, he was invited to work at the Ministry of Finance. He kept this position for 14 months in a few different terms of the government. Under Samsam-o-Saltaneh’s government, he resigned from his adjunct position due to a difference with the Finance Minister (Moshar-ol-Molk) and left to Europe during the inauguration of Vossougho-Dowleh’s second term.

At this period, the 1919 agreement was signed by Vossough-o-Dowleh, while there was a vast opposition coming from libertarians. Mossadegh began to publish articles against the accord. A bit later, as Moshir-o-Dowleh became the Prime Minister who replaced Vossough-o-Dowleh, he called Mossadegh back in Iran to occupy the post of Justice Minister.

After having entered from Shiraz on his way back through the port of Bushehr, he was asked to take a certain petition to Tehran, which made him accede to the post of Governor of the Fars province, a position he kept until the coup on 22 February 1920. After this event, he consecrated his time to oppose the putsch by writing articles for, and making speeches to the elite of the time.

Mossadegh never recognised the government that was established by the coup and resigned from his post. In order to protect himself from the putsch’s instigators, he took refuge in the Bakhtiari tribe and benefitted from the hospitality of its’ khans until the fall of that government.

Mossadegh never recognised the government that was established by the coup and resigned from his post. In order to protect himself from the putsch’s instigators, he took refuge in the Bakhtiari tribe and benefitted from the hospitality of its’ khans until the fall of that government.

With the defeat of Seyd-Zia’s cabinet, Qavam-o-Saltaneh was named Prime Minister. He chose Mossadegh as his Finance Minister. After the fall of Qavam’s cabinet and the accession of Moshiro-Dowleh’s, he was asked to become the governor of Azerbaijan. Due to a transgression by the commander of the groups of this province, he resigned from this post with an order from Reza Khan, War Minister at the time, and returned back to Teheran.

In May 1923, he was named Foreign Minister in Moshir-o-Dowleh’s cabinet. He vehemently opposed a British demand of £ 2 million that pretended having spent that much to create the police force in the south of the country. After Moshir-o-Dowleh’s resignation, “Sardar Sepah” (Reza Khan) became Prime Minister and Mossadegh refused to cooperate with him.

In the same year 1923, Mossadegh wrote his book “Parliamentarian Law in Iran and Europe.” He was also elected at the fifth and sixth parliaments as Teheran’s representative. He was one of the only deputies to oppose the plan to bring the Qajar dynasty to extinction. His reasoning was that the Sardar Sepah would either have to limit himself to the duties assigned to him by the constitution, or he would become a dogmatic leader and the constitution would be put in question. With the end of the Qajar dynasty, the Sardar Sepah, who was Prime Minister at the time, became king.

The sixth parliament having reached its end with the beginning of Reza Shah’s reign, Mossadegh took a more stay-at-home role, having been put under surveillance in his Ahmad Abad estate until 1940. He was also forbidden to teach at university level. He was even imprisoned towards the end of Reza Shah’s reign; however, Ernest Peron (the heir-to-throne’s friend) obtained his freedom after a few months and he returned to Ahmad Abad once again, under surveillance. In 1941, after the occupation of the country by Soviet and British forces, Reza Shah was forced to abdicate in favour of his son and was exiled to South Africa. Thus, Mossadegh returned from Ahmad Abad to Teheran.

After the events of September 1941 and Reza Shah’s downfall, he was elected as the First Deputy of Teheran at the parliament’s fourteenth elections. In order to confront the Soviet Union in its’ push to obtain the rights for the oil in northern Iran, he passed a law that forbid the government to discuss oil rights while foreign forces occupied Iran.

Mossadegh couldn’t participate in the elections of the fifteenth parliament due to an intervention by Qavam-o-Saltaneh and the army. During this period of the parliament, the goal of those parliamentarians who were close to Britain was to validate a contract signed by the government of Saed-Maragheyi during the reign of Reza Shah. With the pressure of public opinion, the efforts of a minority (four deputies) and daily discourses held by Hossein Makki to encounter the project, the goal of the British did not see the day and the fifteenth term of the parliament ended. In 1949, Mossadegh and his friends Ahmad Makki (Editor-in-Chief of the Setareh newspaper), Mohammad-Hassan Kaviani, Karim Panjabi, Ahmad Zirak-Zladeh, Abbas Khalili (Editor-in-Chief of the journal “Eqdam”), Amidi-Nouri (Editor-in-Chief of “Daad” magazine), Seyed Ali Shayegan, Shamseddin Amir-Alaee, Seyyed Mahmoud Nariman, Arsalan Khalatbari, Abolhassan Haeri-Zadeh, Hossein Makki, Mozaffar Baghaee, Abdolqadir Azad, Jalali Nayini (Editor-in-Chief of the “Keshvar” journal) and Hossein Fatemi, founded the “Jebhe Melli” (the National Movement). The broadening of political activities after August 1941 brought an increasing popular battle and a widening attention on the oil contract with it. Mossadegh was at the helm of this movement, which took the title of “the oil nationalisation movement” thereafter; both inside and outside the parliament.

During the elections of the sixteenth assembly in 1949, Lieutenant-General Haji-Ali Razmara attempted to have people close to him inside the parliament. Mossadegh and his entourage in the National Movement manifested at the royal court to ask of the Shah to disallow the interference of the army in political affairs. These elections ended with Razmara’s victory (Razmara was later elected as Prime Minister in the same assembly). But with the help of General Fazlollah Zahedi, chief of police and Razmara’s longtime rival, and the Shah’s implicit protection, as he considered Razmara as his number one enemy at the time; the Tehran votes were invalidated first and then the National Movement minority entered parliament with 8 of the 12 Tehran seats.

In 1950, The Majles minority severely opposed Prime Minister Razmara, who was thinking of entering into an agreement with the British regarding oil. This ultimately brought the approval of the law nationalising Iranian oil.

With the endorsement of the oil contract by the Shah and its’ formalisation, Hossein Ala, the successor to Razmara as Prime Minister, resigned from his powers. At this juncture, the Shah nominated an old anglophile politician, Seyyed Ziaeddin Tabatabai to this post. However, at the parliament, a representative on the court’s side proposed the position to Mossadegh; who, unlike other times, accepted it under the sole condition that in the same debate, the law on the eviction of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company be approved. Finally, Mossadegh’s government was able to obtain the Majles’ vote of confidence with 99 votes for from a total of 102 on 5 May 1951.

Mossadegh immediately proceeded to expulse the British by sending Hossein Makki and Mehdi Bazargan to Abadan. The eviction of the company brought the opposition of the British government with it. After the former launched a formal complaint at the United Nations Security Council, Mossadegh went to New York to defend the rights of the Iranian people. This ended in favour of Iran, as the Council decided that the quarrel was between a government and a company and not between two governments, so it was not qualified to take either side. A year later, Mossadegh went to The Hague to respond to the complaint of the oil company. The court’s judge, a Britton by the name of Sir Arnold McNair, did not recognise the validity of the plaintiff’s demand either and Mossadegh succeeded in making the rights of the Iranian people stand. Iran’s attorney in this case was Henri Rollin, previous Head of the Belgian senate. He asked for no payment in taking the case. Hossein Aliabadi of Tehran University aided him in the task. The defence speeches in this court were made by Mossadegh himself.

Mossadegh immediately proceeded to expulse the British by sending Hossein Makki and Mehdi Bazargan to Abadan. The eviction of the company brought the opposition of the British government with it. After the former launched a formal complaint at the United Nations Security Council, Mossadegh went to New York to defend the rights of the Iranian people. This ended in favour of Iran, as the Council decided that the quarrel was between a government and a company and not between two governments, so it was not qualified to take either side. A year later, Mossadegh went to The Hague to respond to the complaint of the oil company. The court’s judge, a Britton by the name of Sir Arnold McNair, did not recognise the validity of the plaintiff’s demand either and Mossadegh succeeded in making the rights of the Iranian people stand. Iran’s attorney in this case was Henri Rollin, previous Head of the Belgian senate. He asked for no payment in taking the case. Hossein Aliabadi of Tehran University aided him in the task. The defence speeches in this court were made by Mossadegh himself.

The seventeenth parliament elections were held with much friction. These went so far that Mossadegh had to stop them due to the interference of the army at the royal court despite an order to the contrary. Thus, during the Majles’ seventeenth term, many big cities such as Shiraz, Esfahan, Mashhad, the Khuzestan province and parts of Mazandaran and Kurdistan, Hamedan and Luristan were not represented and 55 seats remained empty. Once he got back from the Hague, Mossadegh got elected with 52 votes for, 3 against and 10 abstentions on 10 July of the same year.

With the beginning of the new term in July 1952, Mossadegh asked the Shah if he could himself choose the Minister of War, asking him as well to partake the responsibilities of this ministry with the person he would choose. The Shah told him, “well then tell me straight that I should make my suitcase and simply leave the country!”

The discussions that took place between the kind and Mossadegh concerning the subject led to nowhere and Mossadegh had to resign on 16 July. This resignation concluded into the events of 21 July 1952 that left many dead. Ghavam-o-Saltaneh in turn resigned from his post as Prime Minister, as the Shah didn’t favour his request to dissolve the parliament. Mossadegh consequently took this function back with 61 votes for out of 64.

This period was accompanied for Mossadegh with confrontations opposing him to the Shah, to the degree that, with the events of the following month, the Shah signed two different decrees, one discharging the Prime Minister and the other replacing him with the General Zahedi on 14 August 1953, according to a CIA plan called TP AJAX. The commander of the Imperial Guard, Colonel Nassiri, was asked to deliver the first decree of the Shah by blocking the way of Mossadegh’s house. Elsewhere, other members of the same guard were charged to arrest several Ministers working with Mossadegh. At the same time, groups in the army occupied the telephone center in the Tehran Bazar in order to stop the way of communications. Mossadegh learned about this plot through the military network of the Tudeh (communist) party and their leader, Kianoori.

Colonel Nassiri, who had been to Mossadegh’s house to notify him of the Shah’s order, was arrested by the army forces in charge of guarding the Prime Minister’s house, led by Colonel Momtaz and Captain Fesharaki, and his men were disarmed.

The next day, Mossadegh informed the population that a coup d’état against the government had been unfolded and neutralised, but did not mention the Shah’s order at all. On the same day, news of the Shah’s exit from the country and his flight to Baghdad propagated. Hossein Fatemi ordered all Iranian embassies, including the one in Baghdad, to confront the Shah. From this day on, the Tudeh forces began creating a certain tension in Tehran with their presence. On 17 August, the two groups of Tudeh and the National Movement organised heated gatherings against the Shah. In the one taking place at Baharestan square, with Mossadegh not being present, his friends Fatemi and Saleh attacked the Shah in their discourse in an unprecedented way. Fatemi also accused the Shah of treason in his editorial in his Bakhtar-Emrooz newspaper. Supporters of the National Movement also proceeded to take down statues of the Shah and his father in the Iranian capital’s squares.

Because of the turbulence that occurred on the 17 and 18 August, Mossadegh ordered General Modabber, the Chief of police, to confront any manifestation for or against the Shah or the government. That same day, the ambassador of the US in Iran, Louis Henderson, returned to Tehran and let Mossadegh know of the ultimatum issued by this country, telling him that the United States will not recognise the legitimacy of his government in case of an entente between the latter and the Tudeh party.

On the day of the coup, 19 August, another event led to the overthrow of Mossadegh’s government. According to his book named “Counter Coup”, the CIA agent Kermit Roosevelt affirms that buying the fatwa of a few members of the clergy and paying members of the military and gangsters in Tehran، helped reverse the situation. In these operations, American advisors present in Tehran had their vehicles were used to transport men from the imperial guard towards Mossadegh’s home in order to facilitate the attack. The Americans, in fact, paid active elements of the coup in US Dollars according to the same book.

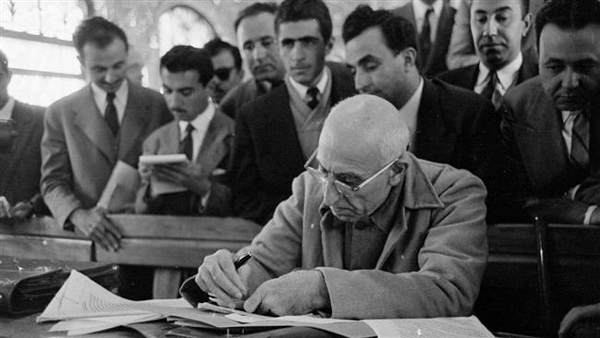

Mohammad Mossadegh was court-marshalled after the events of 19 August and, as he was not recognised guilty in the major accusations brought against him (as attempting to overthrow monarchy and leading a coup against the constitution), was condemned to three years in solitary confinement. Having finished his term in prison, he was exiled to his property in Ahmad Abad, where he was under severe surveillance.

Finally, on 5 March 1966, Mossadegh passed away. He had asked before his death that he be buried by the victims of the 21 July 1952 (“30 Tir”) uprising, but the Shah did not give his consent to Mossadegh’s last wish. His body was then enshrined in one of the rooms in his Ahmad Abad property.

During his last days, Mohammad Mossadegh described the events of 1953 this way: “They made an excuse of Communism to loot our oil reserves for another 100 years. The military court condemned me to three years of solitary confinement that I had to endure in the jails of the second armoured division of the army. On 3 August 1956, the day this period ended, instead of liberating me, they sent me to exile in Ahmad-Abad where a group of soldiers and sergeants were ordered to have me under surveillance. Even now in 1960, I am still under guard; and since they will not let me out of this fortress without an escort, I have chosen to remain in it and have nothing else to do but submit to this fate and wait for my life to end so I could liberate myself.”

Mossadegh is, without a doubt, an Iranian national hero who put everything he could on the line for his country’s honour and the safeguard of its’ national interests, which had been in the hands of imperialism.

His quiet end in Ahmad-Abad did not take anything away from the magnitude of the service he rendered to his country and he has remained a source of pride for the Iranian people.

2004 - Second Mossadegh Prize Laureate - Book

2004 - Second Mossadegh Prize Laureate - Book 2009 - Third Mossadegh Prize Laureate - Book

2009 - Third Mossadegh Prize Laureate - Book 2010 - Fourth Mossadegh Prize Laureate - Book

2010 - Fourth Mossadegh Prize Laureate - Book 2013 - Fifth Mossadegh Prize Laureate - Book

2013 - Fifth Mossadegh Prize Laureate - Book 2015 - S

2015 - S

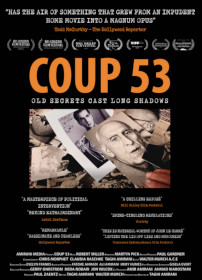

2022 - Eighth Mossadegh Prize Laureate - Film

2022 - Eighth Mossadegh Prize Laureate - Film