Bayat, a Turkish tribe, is one of the 22 'Oqoz' tribes spread out in Iran, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Turkey, Syria and Iraq. The word 'Bayat' means "one who possesses" and "one who brings benedictions." The original tribe, in the legendary Turkish genealogy, reaches "Bay At", second son of Goune Khan, himself the son of Oqoz Khan.

The Bayat tribe, like other Turkish tribes, had its' own ensign carrying different figures according to different sources. The Bayats used to live, before their massive immigrations to West Asia, around the Qaramouran river in northern China.

According to "Jame-o-Tavarikh," groups belonging to this tribe known under the name 'Bavayet' had become a category of Mongol tribes, this having happened decades before Genghis Khan's reign. These used to be, in the categorisation that was proper to Mongols, "Dornegin" tribes, which means "Mongols without a lineage". The two branches of this tribe were named "Jedi Bayavet" and "Kahron Bayavet". The first holds its name from river Jedi in Mongolia et the second, since it lived in the desert. These two tribes participated in Genghis Khan and Holaku Khan's military campaigns in Iran.

In the sixth and seventh centuries, a large tribe that belonged to the "Yamak" or "Kimak"branches of the family named "Bayavout" lived in the Kharazm desert. Because of the assignment of Tarkan Khatoun, mother of Sultan Mohammad Kharazm-Shah, and that of Ozloq-Shah's mother (Ozloq-Shah being Sultan Mohammad's crown prince), the emirs of this tribe won major power in Kharazm-Shah's court; to the point where Qatloq Khan, competing for the place of Sultan Mohammad Kharazm-Shah, tried to assassinate the former in favour of Ozloq Shah. Meanwhile, one cannot equal the Bayats and the Bayavouts with certainty. Mojtaba Minavi, in his writings on the character of Jalaleddin Mirkebreyi, has questioned whether there in fact was a link between the family names. A few researchers have recently stipulated that Bayavouts were not Mongolian tribes, but the same as Turkish Bayats.

The date of entry of the Bayat tribes in the Iranian plateaux is not clear, but according to several historical sources, there is a possibility that these people spread in the highlands of Iran in the early fifth century during the attack of the Qazan and the Seljuk who, in their military dash, had reached the desert of Shaam and the borders of the Mediterranean. In these breakthroughs, groups belonging to this tribe settled in the greater Khorasan, Persian Iraq, Kurdistan and Lorestan. Ibn-Khaldoun informs us of a long term establishment of this tribe in Iran and the Arabian Iraq. The disputes that took place between the Bayats and the Lor tribal chiefs eventually brought the extinction of the Bayats. Abated Shojaeddin Khorshid Shah, the governor of Lorestan, being furious about the encroachment of the Turkish Bayats on his possessions, took them to battle and overtook them; and the Bayat territory became part of Khorshid Shah's sphere of power. At this point in history, the name of the Bayat territory was considered one of the important domain names like Bagdad, Arabian Iraq, Khuzestan and Lorestan. With the passage of time, the name of this territory referred to a more restricted circle that comprised the Bayat castle as its' culminant spot — a castle that was situated on the road between Dezful and Arabian Iraq.

Some Bayats who, in their long migration had reached Anatolia and Shaam, joined Qoreh Ottoman, the governor of Aq-Qovinlou. After the extinction of the Aq-Qovinlou dynasty, the Bayat clan joined the Safavid dynasty once more. Eventually, many tribes left Anatolia and left towards Iran. This group of Bayats named itself Qoreh-Bayat later so that they could be distinguished from the Bayats that remained in Iran. On the same principle, the tribes that remained in Iran were named Aq-Bayat or Bayat-Motlaq ("absolut Bayat"). Apparently, the division of Shaam Bayats that formed the Qajars and the heads of this tribe were part of the lords of Fath-Ali Shah's court.

The heads of the Bayat tribes in Persian Iraq (named "Iraq Ajam") who were considered part of the biggest groups of Aq-Bayat, were counted as illustrious members of the Safavid government during the reign of Shah Tahmasb I (1551-1605). Even the damages that were inflicted upon the tribe by the Shah didn't stop their submission to the royal court.

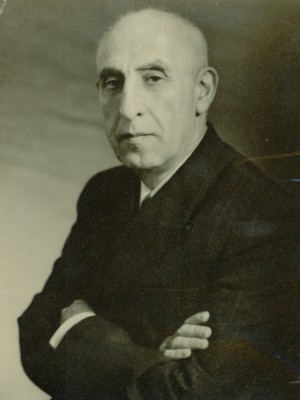

Two centuries later, one of the groups of this tribe joined Aqa-Mohamed Khan Qajar (ruled 1831-1832) and thereby became one of the illustrious members of the Qajar court. One of the most well-known ones who lived at the time of the reign of the Nassereddin Shah (ruled 1885-1934) was named Ali-Naqi khan Bayat and titled Nizam-Lashkar or Samsam-ol-Molk, and was one Iran's biggest feudal barons while at the same time at the helm of a large armed group. His sons Zolfaqar Khan (Samsam-ol-Molk) and Abbasqoli Khan (Sahm-ol-Molk) were, like their father, considered as some of the illustrious people of their era. Morteza-Coli Khan Bayat (Saham-ol-Soltan), who became a parliamentarian several times and even twice minister and prime minister, was the son of Abbas-Qoli Khan.

In our days, all of the Bayat tribes from Iraq Ajam (Persian Iraq) live around Kazzaz and Karamrood and a few other villages of Arak, and make their living with agriculture. Other tribes who live in Maku live there since the reign of Shah-Abbas I (ruled 1616-1658), or emigrated there around the start of Shah-Abbas II's reign (ruled 1671-1698), going there from Yerevan.

Another group of the Bayat tribes had established itself in Iraq's Kurdistan. Shah Tahmasb II (ruled: 1756-1766) sent them to exile around Teheran and Savejbolaq, near Karaj. In 1765, Nadir Shah who at the time was still an attorney of Shah Tahmasb II's court, sent another group of this tribe to Khorassan after having conquered Kirkuk. Nadir Shah also exiled groups of Bayats, Afshars, Javanshirs, Shahsouns and Bakhtiaris to Afghanistan. The majority of this group established itself in Kabul and named itself Qezelbash. The Qezelbash neighbourhood of Kabul is a reminder of this group.

Another part of these tribes that was present in Iran since the tenth century is composed of Neyshabur's Bayats and made itself known under the name Qoreh-Bayat. The exact date of entry of this tribe into Khorasan is not known, but one can safely assume that this group went there after the Mongolian attacks. Abbas Khan Bayat-Mokhtari, Jafar Khan and Aliqoli Khan are well-known names of this part of the tribe. The three were, one after the other, the governors of Neyshabur until the beginning of the reign of Fath-Ali Shah Qajar.

There still recently were nomadic branches of Bayats among the Khamseh and Qashqai tribes of the Fars province alongside the Turkmens of the north of Iran. Beside these populations, thousands of urban and rural Bayat families live in Zanjan, Teheran, Karaj, Shiraz, Zarand, Kerman, Mashhad, Neyshabur, Arak, Damavand and other cities in Iran.

After having been spread out in the cities and provinces of Iran, the Qajar governors who wanted to weaken them, aimed at dividing them into smaller groups. The only remaining well-known Bayats who could keep their authority were the Bayats of Kazzaz (a province of Arak). This branch of the family attained high posts in government in the Qajar dynasty and even later under the reign of the Pahlavis. It could also make the name Bayat live through its' donations; mainly schools, hospitals and other contributions in Arak and its' surroundings.

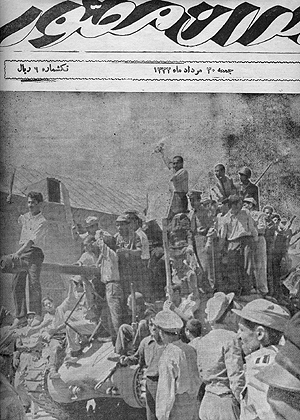

Mossadegh Foundation

Mossadegh Foundation

The Iranology Library of the Mossadegh Foundation is open to the public all year-long except for local public holidays.

The Iranology Library of the Mossadegh Foundation is open to the public all year-long except for local public holidays.